Infinite Creativity

Exhibit co-curator Carin Berkowitz examines tapeworms that Leidy, a leading parasitologist, preserved.

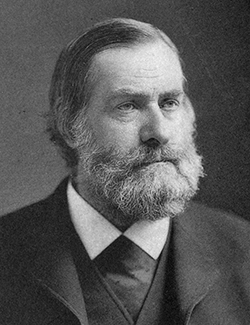

How’s this for a legacy: The last man who knew everything.

That may smack of hyperbole, but only until you read about Joseph Leidy, Swarthmore’s first professor of natural history. In 1871, Leidy established the College's Department of Natural History, where he taught until 1885.

Leidy founded vertebrate paleontology in America, mounting the first dinosaur skeleton. He was the authority on microscopes, becoming the first to solve a murder mystery with one. He conducted the first known tissue transplantation, discovering that human cancer could grow on a frog.

But more than anything, he was a walking encyclopedia, drawing throngs to hear him speak about everything from jewels to parasites, and challenging students to stump him with obscure artifacts.

“His knowledge was immense in breadth,” says Leonard Warren, emeritus professor of cell development and biology for the Perelman School of Medicine, who literally wrote the book on Leidy.

“He had his fingers in about 100 pies, casually from day to day, hopping from one thing to another,” adds Warren. “He was just infinitely creative, and an insipient experimentalist.”

The fruits of that experimentation will be on display in McCabe Library all this month, comprising an exhibit, “Joseph Leidy and the Foundations of Philadelphia Biology,” tied to the College’s sesquicentennial. Howard A. Schneiderman Professor Emeritus of Biology Scott Gilbert suggested the exhibit to acquaint students with Leidy and his “critically important” work.

“I hope people will come away from it with respect for a remarkable teacher, a scientist who excelled in several fields,” Gilbert says. “He’s a great model of a teacher-investigator who was always excited about what he did and could make discoveries from the Badlands of North Dakota to Crum Creek.”

While Leidy’s feats and forays may be difficult to fathom, his mission aligns with Swarthmore’s, says Carin Berkowitz, director of the Beckman Center for the History of Chemistry, who curated the exhibit with Gilbert.

“Leidy put teaching at the center of his scientific work,” she says. “He became the center of an extensive and far-flung community, building connections across the country and the world by maintaining vast correspondence networks. Perhaps most importantly, Leidy took skills from across various subjects and applied them with a passion where he saw the opportunity.”

Berkowitz culled from thousands of documents, artifacts, and specimens to create a visually dynamic display. She borrowed from the archives of Philadelphia as well as the Academy of Natural Sciences and the Wagner Free Institute of Science, for which Leidy served as curator and president, respectively.

“It was fun to think about how the various media could be brought together with my historical work to tell a story,” says Berkowitz.

Among the eye grabbers are fossils that Leidy identified, jars of tapeworms he preserved, and an assortment of sea creatures and skulls.

“It’s almost a ‘Cabinet of Curiosities,’” says Susan Dreher, Swarthmore's visual resources and initiatives librarian, who managed the logistics of the exhibit to bring the curators’ vision to life. “Kind of Mütter Museum-like.”

“A biology exhibition is something different for us, which is really exciting,” Dreher adds, “while still touching on other disciplines.”

Highlights also include a series of scientific illustrations Leidy rendered. They amaze historians not just for their scientific detail but aesthetic sensibilities.

“He was a phenomenal artist who used his drawing ability to further natural history and comparative anatomy,” says Berkowitz.

Professional and personal correspondence and hand-drawn teaching charts imbue humanity into Leidy’s story, too. He took personal responsibility for his students’ learning, advocating for the higher education of women and helping some become the first female physicians in America.

“He always enjoyed learning, always enjoyed teaching, and he was incredibly good at both,” says Gilbert.

Leidy was “supremely humane,” adds Warren, widely and purely admired by his peers. A favorite anecdote arose from a frog dissection Leidy ran one Friday in his Swarthmore biology lab. After returning home, he realized the leftover frogs wouldn’t survive the weekend with no one there to feed them, so he walked back to Swarthmore from center city Philadelphia and released them into the creek.

“That tells you something about the man,” says Warren. “He was quiet, he was unassuming, he didn’t toot his own horn. But those who knew him knew he was the very best.”

The exhibit runs through October in McCabe Library. On Thursday, Oct. 2, at 4:30 p.m., there will be an opening reception with remarks from Berkowitz and Warren.